On April 17, 1975, the Khmer Rouge, under the leadership of Pol Pot, took control of Phnom Penh, the capital city of Cambodia. Over the course of the next four years, the Khmer Rouge murdered nearly two million people while attempting to establish a strictly Communist society.

The Khmer Rouge sought to transform Cambodia into an agricultural utopia void of class and religion. In pursuit of their fanatical goals, they killed leaders of the former government and forcibly relocated millions from urban centers to the countryside to work as slaves digging canals and tending crops. Hundreds of thousands of people died from disease, starvation, and exhaustion after being worked in horrible conditions.

The movement targeted anyone with an education—doctors, educators, journalists—the wealthy, the middle-class, and several ethnic and religious minorities. The regime even killed thousands of its own, claiming that these individuals may have been traitors or spies working for the enemy.

Initially, many of those targeted were imprisoned in special centers, the most notorious being the S-21 jail where 17,000 people were imprisoned while the regime was in power. As the number of captives increased, the Khmer Rouge began developing “killing fields,” sites all over Cambodia where the captured were taken to be killed—frequently after having been tortured. Roughly 20,000 of these mass graves have been uncovered.

Ultimately, Vietnam invaded Cambodia in 1979, overthrowing the regime. It was not until 2006 that the United Nations inaugurated a joint tribunal, the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC). In 2014, Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan, both top leaders in the Khmer Rouge, were found guilty of crimes against humanity by the ECCC.

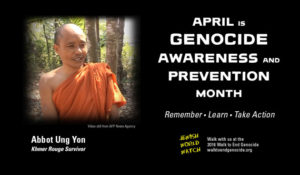

The video below, provided by the AFP News Agency, illustrates the difficulty Cambodians have had recovering from this tragedy—particularly as perpetrators and victims live side by side.