In March 1992, the Republic of Bosnia-Herzegovina declared independence from The Federal People’s Republic of Yugoslavia. The event followed a series of incidents that would ultimately culminate in the breakup of Yugoslavia. Bosnian Serbs however, were unhappy with the newfound independence. They wanted to be part of a dominant Serbian state—and not a state with a Bosniak, or Bosnian Muslim, majority. In April, when both the European community and the United States acknowledged the Republic’s independence, Bosnian Serb leaders severed governmental ties and established their own entity, later titled Republika Srpska.

During the resulting Bosnian War, Serbian separatists in Bosnia, with the backing of Serbian party leader Slobodan Milosevic and the Yugoslav army, bombarded the capital of Sarajevo in what is referred to as the “Siege of Sarajevo.” In the attack, the Bosniak population suffered attacked by snipers who shot at civilians as they tried to get food and water, mass executions, confinement in concentration camps, systematic rape, and forced removal. These attacks against both Bosniak and Croatian civilians, was later described as amounting to ethnic cleansing. By the end of 1993, Bosnian-Serb forces were in control of about three quarters of the country and most of the Bosnian Croats had left the country.

In 1993, several safe zones—areas intended to be protected and off-limits for military targeting—were established by the United Nations Security Council, and authorized the UN peacekeeping force UNPROFOR to protect inhabitants from Bosnian Serb forces. On July 11, 1995, Bosnian Serb forces led by General Ratko Mladic advanced on Srebrenica, attacking Bosniaks seeking safety at a UN base north of the town. Serbian forces then proceeded to separate the Bosniak civilians in Srebrenica, putting the women and girls on buses and sending them to Bosnian-controlled territory and leaving the men and boys behind. Many of the women on these buses were raped or sexually assaulted, while the men and boys who remained were killed or transferred to mass killing sites. An estimated 7,000 to 8,000 men were killed during the specific attack. Those who were not killed in the first massacre were later sent to concentration or detention camps in which they suffered torture, mass executions, and rape.

Take a few minutes to watch this BBC video, which describes the series of events that led to the genocide in Srebrenica:

NATO, in collaboration with the United Nations Protection Force, enacted a bombing campaign targeting the Bosnian Serbs. Known as Operation Deliberate Force, the campaign was instrumental in pressuring a U.S-led peace negotiation to end the war in Bosnia-Herzegovina; the resulting peace agreement is known as the Dayton Accords. By the time the violence subsided, about 100,000 people had been killed (80% of whom were Bosniaks), 20,000 were missing, and two million had fled as refugees.

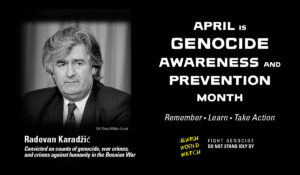

In May 1993, the UN Security Council established the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) at the Hague—the first international tribunal since the Nuremberg Trials and the first to prosecute individuals with crimes of genocide. On March 24, 2016, Radovan Karadzic was found guilty of counts of genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity in the Bosnian war, including the genocide in Srebrenica. Bosnian Serb military commander, General Ratko Mladic was also among those indicted by the ICTY for genocide and crimes against humanity. The ICTY charged more than 160 individuals of crimes committed during conflict in the former Yugoslavia. Similar to the Nuremberg trials, high-level officials, as opposed to all individuals involved in the killings, were targeted.

Watch Christiane Amanpour, CNN’s international correspondent as she reflects on the genocide and the acts of the genocideres in 1995: